Note: The following post was written by Megan Doherty, Washington and Lee University class of 2019, who worked on this project in Summer 2017.

Introduction

Marguerite “Meg” Steinheil was a captivating woman. Of that we have little doubt, and the newspapers cast her as a sensational actress within the narrative of the affair. During the first day of the trial on November 3rd, 1909, Meg entered the world outside Saint-Lazare again for the first time since her imprisonment in November of 1908, only a year prior. This moment stole the show, and the journalists used this entrance as a climactic moment in their coverage. By using unusual verbs, adjectives, and nouns, several of the newspapers were able to build Meg’s story into a thrilling and enthralling narrative. In emphasizing her physical appearance, her body, her voice, her gait, and her youth, the newspapers shifted the emphasis of the trial onto her as opposed to the stricter questions of innocence and justice. The journalists managed to make Meg into this scandalous celebrity, but one onto whom society could place very little blame. Within the articles, the writers took creative liberties and devoted, on occasion, more space to describing the way she looked than her actual interrogation. We need to ask what this says about French society at the time and the era’s hierarchy of moral priorities.

Making An Exposition

The newspaper articles set the stage for drama, quite literally. Meg Steinheil’s entrance into the courtroom became a climactic moment within the narrative of the first day of the trial. Many of the articles describe the energy of the night before the trial; viewers were lined up outside the Dépot, clamoring to get a glimpse of Meg during her societal debut after a year of imprisonment. We see this in the November 4th issue by Le Petit Journal where there is an entire section titled “Devant Les Grilles”[1] before Meg enters the article. One line in particular under this section captures how people came, in waves, to try and gain a seat within the trial:

Peu à peu, deux autres vendeurs de places arrivèrent puis d’autres, puis d’autres encore, décidés à passer la nuit à la belle étoile pour gagner quelques pièces blanches le lendemain matin.”[2]

This excitement serves as a sort of exposition building up to the moment when Meg opens the door to the courtroom, accompanied by guards, and stands before her audience. Some newspapers go so far as to detail and explain the high demand and prices for buying and selling tickets before the trial, demonstrating to what lengths the journalists were willing to set a scene for their readership, and the degree to which this trial was a societal event. For example, Le Petit Parisien included in their section titled “Première Audience D’Un Procès Sensationnel”[3] detailed information on ticket prices:

Disons tout de suite que ces prix ont été loin d’atteindre un chiffre exorbitant. On avait parlé de 1.300 francs, 1.000 et 500 francs. Nous pouvons affirmer qu’aucune place n’a été cédée pour un prix supérieur à 50 francs, ce qui est déjà beau.[4]

Literary Parallels: Meg and Nana

This element of the trial is not unlike the beginning of Nana by Émile Zola, completed in 1880, in which the suspense, theatricality, and drama is built up through the the exposition of the narrative. Nana is the story of an actress and courtesan, and in this respect she might be seen as being somewhat like Mme Steinheil. At the opening of the novel, Nana’s revolutionary sexuality is heightened by the events that transpired before her arrival in the story. Before the readers meet Nana, she is described as having “something else,” regardless of her inability to sing or act and the fact that she originated in the slums of Paris. The title of the performance in which she is the lead is “The Blond Venus” and the play itself foreshadows much of Nana’s role in the novel, because it opens with Diana and Mars discussing how Venus is causing exceptional trouble between many lovers in the story. Nana then progresses in the story to become this multi-dimensional character whose simple demeanor and humble beginnings create a dichotomy with the alluring, sexual goddess she portrays in the performance. The exposition proceeding Meg’s entrance into the courtroom places a heavy emphasis on her as a character whose introduction is the pinnacle of the story and this entrance is the heart of most of the articles. The sheer amount of attention to her arrival shows how the story became understood more a source of entertainment with a dedicated readership than a criminal trial in Belle Époque Paris. Meg becomes this Nana-esque character, because their roles are almost parallel. Meg’s role as a mistress mirrors Nana’s profession, yet both are able to put on a show and convince their audiences that they possess “something more.”[5]

It’s All in the Verbs

Taking a closer look at the language of the articles, we can see how her entrance into the courtroom is described using a variety of verbs. Some articles narrate her entrance using fairly typical, less vibrant verbs. La Croix says simply “Mme Steinheil apparaît.“[6] There is little meat to this verb; Meg Steinheil appears. What’s so special about that? Others have a little more flair and take creative liberty with her entrance. For example, l’Intransigeant takes the time to make her entrance into a grandiose moment by using the phrase “l’accusée descend dans la salle.”[7] Describing her entrance as a descent places her, quite literally, above the courtroom and those within. This creates an atmosphere in which the jurors, the judges, the lawyers, and the spectators must all turn and shift their gaze towards her, making Meg the center of attention as she glides, to use a verb featured prominently within many articles, across the courtroom to her seat. Le Temps uses a curious verb when it details her entrance by saying, “Mme Steinheil est introduite.”[8] Like a character in a novel or an actress on a stage, Meg Steinheil enters the narrative physically for the first time in a year, and the world is pausing to take notice.

In many of the articles, Meg is seen almost as a show-stopping woman. Several describe the transition from a boisterous, talkative audience to one that watches her enter the courtroom, silenced by her presence. The journalists do a marvelous job of dramatizing this shifting of attention, and Le Journal captures her entrance under a section titled “La Cour et L’Accusée.” The moment is highlighted when they say,

Un grand mouvement d’attention se produit dans la salle au moment où s’ouvre la porte du box des accusés par où doit pénétrer Mme Steinheil. La veuve tragique paraît enfin très calme, très digne, escortée de trois gardes républicains, qui prennent place à ses côtés.[9]

On the other hand, some articles introduce her quite quickly and discreetly, shifting the attention from her entrance to her questioning. These fewrticles take less time to sensationalize Meg and more time to divulge the nitty-gritty of her first interrogation. For example, L’Humanité devotes very little space to her entrance. Ten lines within the first section titled “Mme Steinheil lutte avec l’accusation”[10] are dedicated to both her physical description and her entrance, as opposed to the lengthy expositions crafted in others.

Adjectives Make a Difference

Some of the most common adjectives and nouns used within the articles that are: énergie, fraîcheur, jeunesse, simple, pâle, élégante, charme, innocence, jolie, tranquille, dramatique, tragique, and mince.[11] Looking at these, we see that the adjectives tend to possess positive connotations and most are associated with her youthful appearance. By emphasizing her youth and freshness, the journalists create Meg Steinheil into an alluring character who balances innocence and theatricality in the face of imprisonment and aggressive interrogation. In addition to this, Meg maintains her status as a beautiful, tempting, seductive woman. These positive adjectives preserve Meg in time, creating for the readerships a woman who never fades, who did not wither during imprisonment, and has now made her debut into society just as beautiful as before. These adjectives and nouns are also very notable in the sense that they do not allow for guilt to be placed very easily on Meg, because they align more closely with innocence and pity than guilt. They are not adjectives that could be easily associated with a murderess.

Up Close and Personal

Many of the articles focus on physical descriptions of Mme Steinheil as well. Her entrance into the courtroom became for the articles a very dynamic moment, and a number featured a stronger focus on her body and her beauty rather than the dialogue of the interrogation. Indeed, many of the newspapers even become fairly anatomical or medical in their descriptions of her, dedicating space in their articles to specific body parts (i.e. eyes, nose, lips, waist). L’Intransigeant contains a section in which the journalists start with her head and move downward to describe her clothing:

La tête est fine, plutôt un peu maigre; le front étroit et pur, coquettement auréolé d’une couronne de cheveux châtain sombres à reflex cuivrés, le nez mince est joliment arqué, l’ovale allongé, et sans aucun empâtement surmonte un cou svelte et dégagé; les yeux enfin, de grands yeux allongées et lumineux éclairent cette figure, restée miraculeusement jeune, d’une flamme étrangement brillante. La taille, svelte, droite et souple, se moule dans une robe complètement noire, coupée en carré à la naissance de la gorge et laissant le col entièrement libre.[12]

These sections that focused on her physically form follow chronologically right after the description of her entrance and the audience’s reaction. The articles that give the lengthiest descriptions of her appearance are: Le Radical, Petit Parisien, Petit Journal, Le Matin, Le Journal, Intransigieant, and Figaro. It’s important to note that the articles that seem to dedicate the most space to describing her physical appearance are the four sensationalist, mass dailies. Within these specific articles, the sections devoted to Meg often take up a large portion of the total text, even in comparison to the actual dialogue from the trial, and these segments are often placed towards the beginning of the article. This placement indicates that her physical description was used a sort of “hook” to reel in the audience. This suggests that in some ways, her physicality (and by extension sexuality) was more important than the content of the actual interrogation.

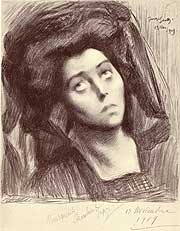

All articles, without fail, mention her dark, black mourning dress paired with a thin, translucent veil that lightly covered her face and eyes. Newspaper images from the time show her as this mysterious woman in black peering forlornly over her veil, obscuring her pale face from the spectators. Her eyes are one of the specific body parts mentioned in almost all of the articles as well, and they are often described as being large and energetic and extremely expressive and alluring. In particular, they are mentioned as being youthful and full of life despite her time in prison. Her eyes stand out against her more gaunt face. Finally, many of the articles touch on their elegance and high-class appearance, something that we will examine later on. For all the journalists, Meg Steinheil’s coloring is one of the few signs that she has spent any time in prison at all. She is described as being pale and anemic in appearance, yet it is reiterated that this does not detract from her beauty.

Meg’s figure is of great import in several of the articles as well. She is described as being slim-waisted and elegant and she “glides” across the courtroom. Young and youthful, one is unable to see that she spent a year in prison, and her beauty and simple physique are often part of the dialogue (throughout the case, she is often described as looking younger than her teenage daughter Marthe at the time). Finally, Meg Steinheil’s voice is another highlighted characteristic in many of the November fourth articles. They place a striking emphasis on the way Meg Steinheil speaks for the first time. It is often described as raspy and caught in her throat. Low and barely audible in the beginning, it becomes clear later on the trial, ringing out and captivating the audience.

Her Hair of Many Colors. Wait, what?

Her hair becomes a rather serious matter in the trial, and several articles discuss how she had it expertly styled in a fashion appropriate for a grieving widow. One of my favorite discrepancies amongst the articles is Meg’s fantastic changing hair color. Her hair changes from a shiny, sleek black to a light blond depending on which article is describing her. Le Temps describes her hair in saying, “les cheveux blonds ondulant sous une sorte de toque ornée d’une couronne,”[13] while Figaro describes her hair as brunette. Finally, in the quote from Intransigeant on page nine describes her hair as being a dark, rich brown color. What does it mean if the articles can’t get something as obvious as hair color correct? An individual’s hair color is something that is relatively easy to determine upon first glance. So why, then, were the journalists unable to come to some sort of agreement on the basics of Mme Steinheil’s appearance? My guess is that because the public had not seen Meg in over a year, she could fill any sort of mold that they desired. If newspapers’ readers were not present at the trial, the journalists had the power to make her into whatever character suited them best. Alternatively, blond hair makes her into someone more pure and trustworthy. In her book Disruptive Acts, Mary Louise Roberts discusses the associated between blond hair and beauty and innocence in this era. Black hair implies some sort of sinister quality, and her hair color could have varied based on the newspaper’s opinion towards Meg.[14]

A Classy Lady

Class differences, a deep and richly complex topic, are personified in these ten articles as well. Meg’s transcendence of class is brought up in subtle (and not-so-subtle) ways. Her social-climbing affairs with wealthy men in order to support her husband’s faltering artistic career are often brought into question during the trial and used as tools to demonstrate that Meg was an unsavory, dishonest woman. Her movement between classes is often discussed through her physical features within a number of these articles. The upper half of her face is seen as being elegant and of a noble class, while the lower half of her face is seen as being rough, hard, and more closely associated with lower socioeconomic classes. We see this division clearly in the November 4th article by Le Petit Parisien when it says, “Ses veux, légèrement cernés, demeurent brillants et beaux. Mais ses lèvres sont contractées, ce qui la vieillit un peu et enlève à sa physionomie une partie de sa grâce.”[15] Extrapolating a little from this, we can see how lower extremities (even the jaw line) have an association with the lower class. This perpetuates the association that those of a lower class are inherently related to vulgarity and, to relate it back to the case, crime. Meg Steinheil’s face encapsulates both worlds. Meg had beauty and bourgeois grace while, at the same time, places her in a lower, crime-ridden class. These differences between the upper and lower portions of her face represent her ability to look the part of an upper-class woman while performing the explicit acts of a lower-class woman during the time period. This may have been why Meg Steinheil was the preferred lover of so many influential men, including the president of France Félix Faure.

All Good Scandals Must End

The case itself shows, from its inception with the 1908 murders, an incredible ability to morph from a police investigation to a celebrity sex scandal. Meg Steinheil’s moment of entrance into the courtroom becomes the climax of the story as opposed to when they finally begin her first interrogation. The audience has gathered to witness Meg, not to find truth, and this is reiterated within the newspapers covering the trial day-by-day. Not all, but most chose to spend a considerable amount of their publishing space focusing on her physical description. This emphasis on Meg is noted within the newspapers linguistically also; the adjectives and verbs suddenly become more theatrical, and they convey a story rather than a criminal case. There is also an anatomical air to the writing style the journalists used. Meg’s physical features become a hot topic of conversation and, in some articles, receive more attention than the interrogation that followed. In the end, Meg’s appearance and beauty overshadowed the actual content of the trial.

[1] “In front of the gates”

[2] “Little by little, two other sellers arrived. Then others, and then others determined to sleep under the beautiful stars in hopes that they would earn coins for the next morning.”

[3] “The first audience of a sensational trial”

[4] We can say right away that these prices were far from an exorbitant figure. There had been talk of 1,300 francs, 1,000 and 500 francs. We can affirm that no place was sold for a price higher than 50 francs, which is already expensive.”

[5] Zola, Emile, and Douglas Parmée. 1992. nana. New York;Oxford;: Oxford University Press

[6] “Madame Steinheil appears”

[7] “The accused descends into the room”

[8] “Madame Steinheil is introduced”

[9] “A great shift of attention is produced in the room at the moment when the door by which Madame Steinheil must enter opens. The tragic widow appears very calm, very dignified, escorted by three republican guards who take their places at her side.”

[10] “Madame Steinheil fights with the prosecution”

[11] “energy, freshness, youth, simple, pale, elegant, charm, innocence, pretty, tranquil, dramatic, tragic, thin.”

[12]“The head is fine, fairly lean; The narrow, pure forehead, coquettishly crowned with a crown of dark brown hair with copper-toned highlights, the thin nose is prettily arched, the mouth elongated, and without any thickening, surmounts a slender neck; finally her eyes, large, elongated, luminous eyes, illuminate this figure, miraculously young, of a strangely brilliant flame. The waist, slender, straight and supple, tightly wrapped in a completely black dress, cut square at the base of the throat and leaving the neck completely free.”

[13] “Her blond hair undulating under a sort of hat with a crown”

[14] Roberts, Mary Louise. Disruptive acts: the new woman in fin-de-siècle France. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

[15] “Her eyes, lightly encircled, remain brilliant and beautiful. But her lips are contracted, which age her a little and removes part of her grace from her countenance.”

Image Credits

Figure 4.1: Agence Rol, Bibliothèque Nationale de France. “A crowd in front of the Palais de Justice in Paris during the trial of Marguerite Steinheil on 1 November 1909.” Wikimedia Commons. Accessed August 2, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Marguerite_Steinheil#/media/File:Affaire_Steinheil,_Palais_de_Justice,_Paris,_1909.jpg

Figure 4.2: Anonymous, “Steinheil explains herself in court.” Wikimedia Commons. Accessed August 2, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Marguerite_Steinheil#/media/File:Steinheil_explains_herself_in_court.jpg

Figure 4.3: By Georges Scott – Madame Steinheil drawing by Georges Scott – 1909 from Christian Siméon La priapée des écrevisses ou L’affaire Steinheil Ed : Crater – 1999, Public Domain. Accessed August 2, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2557584